Multiple XSS in Meta Conversion API Gateway Leading to Zero-Click Account Takeover

Introduction

The Meta Conversions API Gateway is a server-side solution developed by Meta (formerly Facebook) that allows businesses to send web events, such as customer interactions and purchase data, directly from their servers to Meta’s platforms, bypassing traditional browser-based tracking methods like the Facebook Pixel.

This gateway acts as an intermediary that collects, processes, and securely transmits event data from your website or app to Meta. Unlike client-side tracking, which relies on cookies and browser signals, the Conversions API Gateway ensures that the data reaches Meta even if a user has disabled cookies, uses ad blockers, or is affected by browser privacy restrictions. It can be deployed using cloud servers or via Meta’s own infrastructure, allowing for streamlined integration with minimal technical overhead.

Technically, the Meta Conversions API Gateway is open-source technology, which means that any company can deploy it within their own infrastructure rather than relying solely on Meta’s servers. Meta provides the gateway as a containerized application, making it compatible with common cloud platforms or on-premises servers. This setup allows businesses to maintain full control over the data flow, security, and compliance while still sending conversion events to Meta. The gateway is designed to handle high volumes of server-to-server event traffic efficiently.

The Conversions API Gateway gw.conversionsapigateway.com and capig-events.js script

The Conversions API Gateway (gw.conversionsapigateway.com) is Meta’s own hosted deployment of the gateway application. We decided to test against Meta’s gateway directly, since any vulnerability would affect Meta-owned properties immediately.

To support conversion event collection and processing, the gateway serves a JavaScript file named capig-events.js, located at:

https://gw.conversionsapigateway.com/sdk/<pixel_id>/capig-events.js

Within Meta’s infrastructure, this script is not manually embedded by developers. Instead, it is automatically loaded by Meta’s fbq client-side JavaScript module. As a result, it executes on:

- www.meta.com

- business.facebook.com

- developers.facebook.com

- Various third-party customer websites

Any vulnerability in this script therefore inherits the privilege of whatever site includes it.

Bug #1: Trusting event.origin and Turning It Into a Script Loader

The first issue exists entirely on the client side, inside capig-events.js. It only triggers under a specific condition: when the page has an opener window.

If window.opener is present, the script registers a message event listener to receive configuration data for IWL.

window.addEventListener("message", function (event) {

var data = event.data;

if (

!localStorage.getItem("AHP_IWL_CONFIG_STORAGE_KEY") &&

!localStorage.getItem("FACEBOOK_IWL_CONFIG_STORAGE_KEY") &&

data.msg_type === "IWL_BOOTSTRAP"

) {

if (checkInList(g.pixels, data.pixel_id) !== -1) {

localStorage.setItem("AHP_IWL_CONFIG_STORAGE_KEY", {

pixelID: data.pixel_id,

host: event.origin,

sessionStartTime: data.session_start_time

});

startIWL();

}

}

});

This is where the first trust boundary is crossed.

When a message with type IWL_BOOTSTRAP is received, the script checks that the provided pixel_id exists in an internal list. What it does not check is where the message came from.

Instead of validating event.origin against an allowlist, the script stores it and treats it as a trusted host.

Later, during initialization, this stored origin is used to dynamically load another JavaScript file:

<origin>/sdk/<pixel_id>/iwl.js

At this point, the vulnerability becomes clear. The attacker cannot control the path, but they fully control the origin. If they can make the browser accept a script from that origin, they gain arbitrary JavaScript execution in the context of the embedding site.

This is a classic example of a dangerous pattern:

taking unvalidated origin data from postMessage and turning it into code execution.

Why This Is Not Immediately Trivial? CSP and COOP

On paper, Content Security Policy (CSP) and Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy (COOP) appear to limit the impact.

On www.meta.com, CSP does not allow arbitrary external scripts.

Additionally, most pages deploy:

Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy: same-origin-allow-popups

This prevents simple opener-based exploitation.

However, security is not evaluated on a single page or a single policy.

It is evaluated across all contexts where the code runs.

CSP Bypass

In logged-out states, certain Meta pages (notably under /help/) relax CSP to include third-party analytics providers such as:

*.THIRD-PARTY.com*.THIRD-PARTY.net

At that point, the attack surface expands.

A subdomain takeover, XSS, or file upload on any CSP-allowed third-party domain would be sufficient to host an attacker script capable of sending the required message to trigger the exploit.

Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy: same-origin-allow-popups Bypass

When executed inside Facebook’s Android WebView, window.name reuse combined with window.open() allowed attacker-controlled pages to regain access to the opener.

window.name = "test";

window.open(target, "test");

This bypass only ensured that the current window would have an opener object; however, the window becomes its own opener.

In this case, the cross-window message must be sent from one of the page’s iframes.

Iframe Hijacking

Likely, meta.com was loading third-party content such as ads or social plugins hosted in iframes.

We exploited a vulnerability in one of these third-party components to completely hijack the iframe and later send the malicious postMessage from there.

This allowed the attacker-controlled iframe to interact with the parent window (www.meta.com) and deliver a malicious postMessage payload, which eventually triggered the loading of the JavaScript file iwl.js from a CSP-allowed third-party website.

Attack Flow Summary

First, we visit the attacker’s website while logged into Facebook, inside the Facebook App WebView:

0) User opens a url inside Facebook application

1) The script running on the attacker’s website executes the opener bypass

and redirects the user to https://www.meta.com/help/

2) On the help page, the script inside the hijacked iframe redirects to a

(*.THIRD-PARTY.com) page (allowed by Meta’s CSP). The script there sends the

IWL_BOOTSTRAP postMessage to the parent window (www.meta.com)

3) At the same time, the attacker-controlled (*.THIRD-PARTY.com) hosts a

JavaScript file named iwl.js under /sdk/{pixel_id}/iwl.js containing

the XSS payload

4) The script is loaded from the attacker-controlled third-party website

and executed in the context of www.meta.com

Impact

Since this occurs in a logged-out state on www.meta.com and inside the Facebook App WebView, the objective is to escalate this into Facebook account takeover.

We identified an endpoint on www.facebook.com that whitelists www.meta.com in CORS.

From there, it becomes possible to issue authenticated requests, read CSRF tokens from responses, and perform privileged actions such as changing the account’s email or phone number—ultimately leading to full account takeover.

Bug #2: Stored JavaScript Injection in the Gateway Backend

The second vulnerability exists on the server side and is arguably more severe.

After reporting the first bug, I went to take a look at the code. It then came to my attention what the iwl.js JavaScript file that this code attempts to load actually does.

If the file is successfully loaded from https://gw.conversionsapigateway.com,

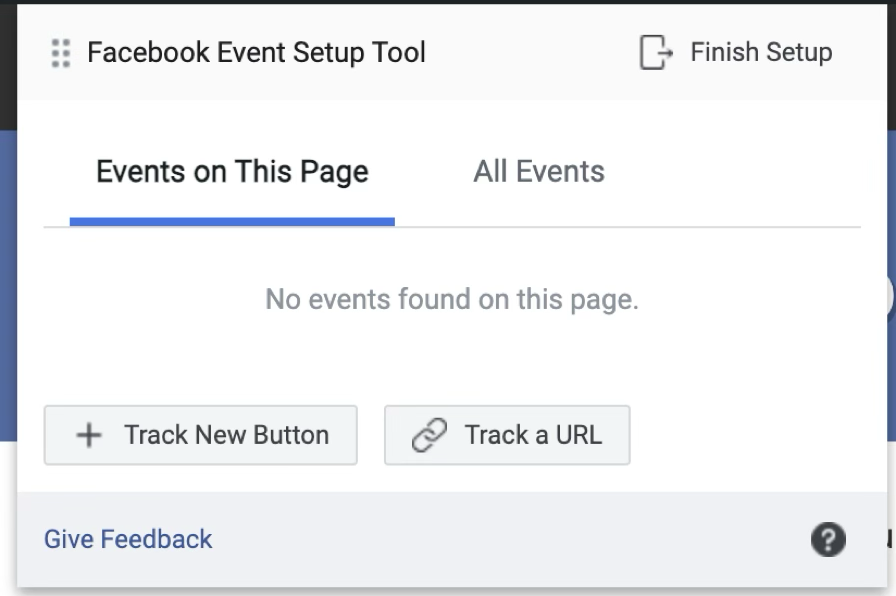

the www.meta.com website displays a graphical tool that looks like this:

While experimenting with the tool, I noticed that it allows creating IWL event rules and parameters.

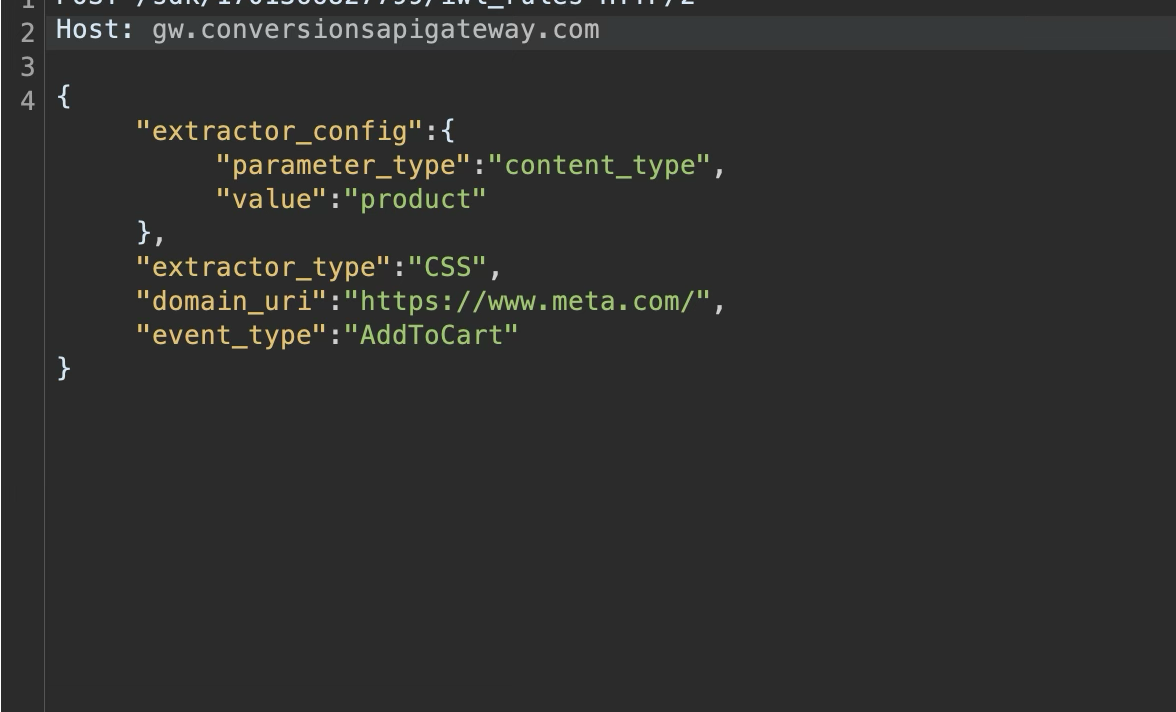

Whenever a new event match rule is added, the tool triggers a POST request.

For example, when a rule is created to match the load event of a page named testing_page, the request returns a 200 OK status code along with a response body containing the ID of the newly created rule. The same behavior occurs for POST requests used to add other IWL rules.

After adding the rules, nothing appeared to happen, at least initially.

At this point, I decided to review the source code, which was publicly available on Amazon ECR.

After downloading it, I found hundreds of libraries packaged as JAR files. To make the code easier to inspect, I extracted all of them and began searching for keywords from the earlier requests.

That’s when I discovered that the logic responsible for generating parts of capig-events.js resides in:

Lib: pipeline-sources-common-1.0.0-SNAPSHOT.jarAHPixelIWLParametersPlugin.java

StringsKt.trimIndent("\n cbq.loadPlugin(\"ESTRuleEvaluator\");cbq.optIn(\"" + this.pixelID + "\", \"ESTRuleEvaluator\");\n "));

StringsKt.trimIndent("\n cbq.config.set(\"" + this.pixelID + "\",\"IWLParameters\",{params: " + paramsCommand + "});\n ");

return extractorCommand;

if (extractorConfig != null) {

String extractorConfigSerilized = serilizeExtractorConfig(extractorConfig);

paramsCommand.append("{\"domain_uri\":\"");

paramsCommand.append(domainUrl);

paramsCommand.append("\",\"event_type\": \"");

paramsCommand.append(eventType);

paramsCommand.append("\",\"extractor_config\": ");

paramsCommand.append(extractorConfigSerilized);

paramsCommand.append(",\"extractor_type\": \"");

paramsCommand.append(extractorType);

paramsCommand.append("\",\"id\": \"");

paramsCommand.append(id);

paramsCommand.append("\",},");

}

Essentially, the code takes JSON keys supplied in the request and constructs a JavaScript string by appending corresponding values.

The calls to cbq.loadPlugin and cbq.config.set were familiar — the same functions are used extensively throughout Meta Pixel and Signals JavaScript files. This raised suspicion that the generated output would eventually be appended to the initial capig-events.js script.

Revisiting capig-events.js confirmed this. At the end of the file, the dynamically appended code was present:

cbq.config.set("1701366827799", "IWLParameters", {

params: {

"domain_uri": "https://www.meta.com",

"event_type": "AddToCart",

"extractor_config": "...",

"extractor_type": "CSS",

"id": "id"

}

});

This confirmed that the script is not static, but dynamically changes depending on which rules or plugins are configured.

Returning to the backend code, a major issue becomes obvious, it concatenates strings using user-controlled values without any escaping.

if (extractorConfig != null) {

String extractorConfigSerilized = serilizeExtractorConfig(extractorConfig);

paramsCommand.append("{\"domain_uri\":\"");

paramsCommand.append(domainUrl);

paramsCommand.append("\",\"event_type\": \"");

paramsCommand.append(eventType);

paramsCommand.append("\",\"extractor_config\": ");

paramsCommand.append(extractorConfigSerilized);

paramsCommand.append(",\"extractor_type\": \"");

paramsCommand.append(extractorType);

paramsCommand.append("\",\"id\": \"");

paramsCommand.append(id);

paramsCommand.append("\",},");

}

Essentially, the code takes JSON keys supplied in the request and constructs a JavaScript string by appending corresponding values.

Exploitation is trivial — injecting a single quote is sufficient to break out of the string context and begin injecting arbitrary JavaScript. By injecting characters such as "]}, attacker-controlled JavaScript is appended to the generated output. The result is a stored XSS vulnerability inside capig-events.js itself.Once injected, the payload is served to every user who loads the script — including visitors to Meta-owned domains.

Why This Matters More Than a Typical XSS

This is not a single-page issue. It is a supply-chain vulnerability in a shared analytics tool. Attackers does not need to trick users into clicking links. They can cause JavaScript execution:

- On

www.meta.com,www.facebook.com,business.facebook.com, and internal Meta domains - Inside authenticated browser sessions

- At massive scale

Once code execution is achieved on a Meta surface, further escalation becomes possible — including interaction with Facebook endpoints, account takeover, and even remote code execution if employees in internal Meta domains were targeted.

Even without immediate ATO, the silent execution of attacker-controlled JavaScript in a globally deployed analytics script is already catastrophic.

Beyond Meta

Because the Conversions API Gateway is open source, any company deploying it and loading capig-events.js from their own gateway may also be vulnerable.

Our research indicates that the application has been deployed at least 100 million times.

Organizations hosting the script on their own domains are therefore exposed to the same stored XSS vulnerability

In practical terms, this meant that within hours, any Facebook user ( or any other user ) visiting virtually any page on the internet ( that includes this script ) could have been silently targeted. Because the vulnerable code executed in trusted Facebook and third‑party contexts, an attacker could have compromised millions of users in a very short time frame, without interaction or warning.

Closing Thoughts

Both vulnerabilities described here stem from the same root problem: treating analytics infrastructure as “low risk” code.

When JavaScript is shared across products, domains, and customers, it becomes part of the platform’s trusted computing base.

At that point, origin validation, strict CSP design, and safe code generation are no longer optional, they are existential requirements.

The Conversions API Gateway demonstrates how small, localized trust decisions can cascade into platform-wide security failures.

Timeline

Nov 22, 2024 — Bug #2 reported

Nov 22, 2024 — Bug #2 Acknowledged by Facebook

Nov 24, 2024 — Bug #1 reported

Nov 25, 2024 — Bug #1 Acknowledged by Facebook

Dec 11, 2024 — Bug #1 Fixed by Facebook

Dec 24, 2024 — $62,500 bounty awarded by Meta for Bug #1

Jan 3, 2025 — Bug #2 Fixed by Facebook

Jan 16, 2025 — $250,000 bounty awarded by Meta for Bug #2